Like a lot of people in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, Stephen Pierson wants to turn back time and undo the waterfront rezoning for Greenpoint (and presumably Williamsburg). Unlike a lot of people, Pierson is running for City Council, so his ideas are getting a lot of attention.

As someone who has spent a lot of time on land use issues in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, and who put a lot of time and effort into fighting for the community’s position on the 2005 zoning and the many follow up actions and subsequent rezonings, I support this idea in concept. In reality, though, Pierson is making promises he can’t keep, and I think he knows it.

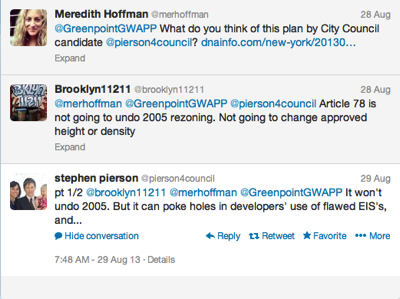

A coalition organized by Levin’s opponent for the Democratic nomination, Stephen Pierson, is pursuing an article 78 lawsuit to block the [Greenpoint Landing] development on the grounds that it is based on a grossly outdated Environmental Impact Statement.

First, let’s be clear about one basic fact – Article 78 is not going to reverse the 2005 rezoning or the Greenpoint Landing Development. The 120-day statute of limitations on filing an Article 78 action ran out almost 8 years ago (7 years and 361 days, but who’s counting?).

So if an Article 78 petition can’t stop the towers on the Greenpoint waterfront, what will it stop? Two things: affordable housing and parks.

There are two current applications going through ULURP – one for Greenpoint Landing and one for 77 Commercial Street. If those applications are approved, one could petition to reverse those approvals under Article 78. But those approvals (which haven’t happened yet) are not the 2005 zoning, so the 40-story towers along most of the Greenpoint waterfront would not be touched. What would be touched is the affordable housing that the city committed to build in the 2005 Points of Agreement (over 600 units between Greenpoint Landing and 77 Commercial) and funding for parks and open space ($8 million), also promised by the city in 2005 (although the city promised $14 million back then). (This is not to say that either of these actions should be approved or are in any way a great deal for the community. In fact, a big part of these current actions are about the city trying to follow through on unfulfilled promises from 8 or 9 years ago, and a big problem with the current actions is the extent to which it gets the city off the hook for a lot more – but more on that later.)

Pierson has already admitted that Article 78 is not going to reduce the as-of-right development on the waterfront from 40 stories to 15 (if it won’t undo 2005, it won’t undo 40 stories), but in articles and on his own campaign website he continues to say that Article 78 challenges are a viable tool in fighting the 40-story towers. To be clear – because Pierson seems unable to do so – IF an Article 78 challenge against the current ULURP applications for Greenpoint Landing/77 Commercial Street was successful, the court would throw out those approvals but the prior (2005) zoning would remain in place. In the case of the current Greenpoint Landing application, 40 stories and 4,000+ units of market-rate housing is the existing zoning. In the case of 77 Commercial, 15 stories and 275 units of market-rate housing is the current zoning. (Article 78 petitions are also very expensive – easily $100,000 or more – and, if SEQRA/ULURP procedures are followed (something that cadres of lawyers and environmental consultants are retained to make sure happens), Article 78 petitions are difficult to win.)

The only way to reduce the height and density of the 2005 rezoning is do a new rezoning (something that Pierson says he will do). Personally, I think this would be extremely hard to do – not turning lead-into-gold impossible, but pretty damn close. You would be fighting against billions of dollars of vested development rights and the vested interests of a lot of labor and affordable housing advocates. Look at the 2010 Domino rezoning, which is actually bigger and denser than the 2005 rezoning, and provides far less open space and arguably less affordable housing – neighbors, community groups and the Community Board fought tooth and nail against this super-sized zoning, and lost.

‘If de Blasio becomes mayor, he might be more friendly to this idea. He might be able to scale back certain parts. In February of 2008, we scaled back, we down-zoned 13 blocks around Grand Street in Williamsburg. So, it’s possible.’

Pierson brings up the Grand Street rezoning a lot, but I don’t think he knows what that rezoning was all about. First off, Pierson had nothing to do with the Grand Street rezoning – his choice of pronouns is frankly insulting to the neighbors, city planners and community leaders (Diana Reyna was the true hero on this particular rezoning) who worked together to curtail the construction of “finger buildings” in Greenpoint and Williamsburg.

But to the substance of his claim, the Grand Street rezoning was actually a fairly small contextual rezoning, one of a series of actions undertaken after the 2005 rezoning in response to the spate of “finger buildings” being erected throughout Williamsburg. In response to these low-density height-factor-zoning towers, the Department of City Planning proposed contextual rezonings for about 200 blocks in Williamsburg and Greenpoint, changing the predominantly R6 zoning to R6A or R6B. The first action was actually a follow-up corrective action (FUCA) to the 2005 rezoning itself that put height limits on buildings along Metropolitan and Meeker Avenues (most of the rest of the 180 blocks rezoned in 2005 were given height limits). The Grand Street rezoning was the second action – about a dozen or so blocks got height limits as part of that action. The third, and by far the largest action was the 2009 Greenpoint/Williamsburg Contextual Rezoning that established height limits on 175 upland blocks from Commercial Street in the north to Maujer Street in the south. As a result of the 2005 zoning and the follow-up actions, about 400 blocks in north Brooklyn are contextually zoned with height limits. Yes, some of the height limits are too tall for some, but they are there.

Grand Street and all of the other follow up actions are completely irrelevant to rezoning the waterfront rezoning for one simple reason – density. None of these rezonings significantly changed the density of development in Greenpoint or Williamsburg. The height limitations were intended to curtail finger buildings and the abuse of the community facility bonus, not to reduce the base density of development. Rezoning the rezoning, on the other hand, would reduce the density of development by a factor of up to 50%. Not that that is a bad thing, but as a precedent for doing so, the scale and scope of the two actions have nothing to do with another.