From Plenty magazine, including a lovely panorama view of North Brooklyn.

About That Oil Spill

DOB Takes Action

Obviously in hasty response to my recent posts, DOB has a series of reforms aimed at improving construction safety in New York City. Actually, the second half of that sentence is true – there’s even a press release. A lot of the press release covers initiatives that have been in place for some time, but some of it does propose new reforms. These include:

Deploy New Staff to Crack Down on Unsafe Construction. DOB will be adding 88 new staff lines to create 7 new special enforcement teams.

Make It Costly to Disobey Stop Work Orders. “If work continues in violation of a Stop Work Order, inspectors will issue violations carrying immediate civil penalties that must be paid before the Stop Work Order may be lifted.” [This one’s for you, 48 Box Street.]

Outline an Aggressive Legislative Agenda to Add Enforcement Tools. “In the next month, Buildings Commissioner Lancaster will outline an aggressive legislative agenda that will call for increased enforcement tools for the Department.”

Increase Safety with Handheld Computers for Inspectors. “…all inspectors will be provided with handheld computers that will allow inspection results and violations to be entered from the field and uploaded immediately to BISWeb for Buildings employees and the public to view in real time. With B-FIRST, the inspection process will be made more efficient and results more accurate, while eliminating delays in reporting crucial safety information at construction sites.”

Set New Standards for Architects and Engineers Who Professionally Certify. “With the New NYC Construction Codes, the Department will reform the professional certification system by establishing standards that licensed architects and engineers must meet and maintain to participate in the program.”

Stop Repeat Offenders from Filing Applications. “Recently-enacted legislation enables the Buildings Commissioner to refuse applications filed by architects or engineers who, after due process, are found to have filed false or fraudulent documents. By refusing applications, the Commissioner prevents the architect or engineer from doing business with the Buildings Department.” [If this means that architects and engineers will not be able to file any applications (as opposed to self-certified applications), it will be something new and improved. Of course it doesn’t address the issue of expeditors, who are not professionals.]

Make Architectural Plans Available Online via BISWeb. “By 2009, the Department will expand B-SCAN’s capabilities so that architectural plans will be scanned and provided online as well.” [Another big step forward, assuming the plans are available immediately – right now, plans seem to go into some deep limbo as soon as permits are issued, making public scrutiny (and challenge) near impossible.]

Enhance Reporting System to Focus on Safety Trends. “…the Department will develop a Compstat-like system to aggressively track safety trends.” [Another major step forward into the 21st century, though why this focuses on safety trends only, and not other complaint categories, is a bit baffling.]

According to Lancaster, all this means that for “the first time in the Department’s 150-year history, we are positioned to transform to a proactive enforcement model…” Which is a good thing, though it does acknowledge many of the main criticisms of DOB over the past few years.

Toll Brothers Reports Big Loss

Where they think there’s no demand, they’ve basically stopped building.

What glut?

Newsflash! There are a shitload of condos in Brooklyn, and we might not be able to sell them all.

There has been massive overbuilding in the entire borough of Brooklyn. It is like the Wild West, and if you don’t control growth, then at some point it’s going to get out of hand.

At some point.

421-a

According to the Sun, the real estate industry is gearing up to have another go at 421-a tax abatements when the topic comes before the City Council in December. Their argument is that the changes in the law (which don’t take effect until July 1) combined with the declining real estate market, will slow development.

I don’t know that the changes to 421-a will actually result in any increase in affordable housing (the stated goal of the changes), but I think the industry is crying wolf here. First off, the changes will have been in effect for less than 6 months come December. Since every developer with a shovel in the ground today is rushing to get vested before June 30 (and thus still operate under the old 421-a rules), there is no doubt in my mind that there will be a slacking off of new construction after June 30 as the industry collects its breath. Add to that a market that is already moving away from condo development, and a market that by all accounts is softening, and you have the makings for a general lull in the second half of 2009. Given all that, I really don’t see how you can argue with a straight face that the new rules are slowing development.

But there is also a question as to whether or not the abatement itself is a zero-sum game. Yes, if the abatement disappears, property values on new condominiums will drop to compensate for the lost abatement. But total monthly housing costs will not change – prices will just adjust accordingly. For example, if I take out a $500,000 mortgage at 7% for 30 years, my monthly payments come to $3,325. For the sake of round numbers, assume that my monthly common charges are $675, and that, with the 421-a abatement, that includes $100 per month in taxes. So my total monthly payment for housing is $4,000. Now take away the abatement and raise my monthly taxes to (say) $600. If my mortgage remains the same, my monthly costs have increased by $500. But, if I am in the market for a new condo, and my total housing budget is $4,000, I am going to look for cheaper housing to compensate for the higher taxes. So instead of affording $3,325 per month in mortgage payments, I can now afford only $2,725 – which works out to a mortgage of about $410,000. So, as a result of the loss of the abatement, my purchasing power has dropped by $90,000 (18%!). That’s horrible!

Or is it? The loss of the abatement effects everyone, so if economic theory holds true, supply will reduce its asking price to meet the new demand. But only on new developments. If I already own a condo with the 421-a abatement in place, that abatement continues. So the price of my condo does not fall. If I am buying vacant land to develop a condo, my offer price will presumably reflect the new 421-a reality. Yes, some people lose out – mainly developers who bought property based on developing condos with the abatement. But risk is part and parcel of real estate development – developers make incredible profits because they take pretty big risks. And anyone purchasing property for condo development in NYC in the past one to three years should have understood the risk of not having the abatement to market.

In the grand scheme of New York City real estate, the number of developers caught in the middle on this has to be pretty small. And therefore, the real effect of this legislation on property values should also be negligible. Yes, selling prices on new condo developments will drop to reflect the increased taxes. But the net effect to the buyer will be zilch – you will still be paying the same amount per month as you would have under the old 421-a rules.

Circling back to the Sun article, the effects of these changes on property values won’t be felt until mid-2009 at the earliest (after all, we are talking about projects that don’t have foundations poured by June 30, 2008). But that won’t stop the industry from crying wolf come December.

Mike’s Out

I’m glad he’s not running, but I think Mike would have made a fine president. I’m sure I wouldn’t have agreed with everything he did (as I haven’t agreed with everything he’s done). Particularly as we try to untangle the fiasco of the last eight years, we will need competent, level-headed leadership.

Maybe he’s available for veep?

Fixing DOB

Sure, its an ambitious title. But, as Reverb says in the comments to Monday’s post, its great to define the problem, but how do you fix it?

First, let’s recap the magnitude of the problem: if you call in a complaint to 311 for illegal after-hours/weekend work, there’s about a one in four chance that an inspector will show up that day. 75% of the time, the inspectors show up days later, when, presumably, the illegal work you called about is long since finished and the inspection is a waste of time and money.

All of this encourages the kind of Wild West mentality that has dominated construction in Williamsburg and Greenpoint for years. If the odds of getting caught doing illegal work are low, and the penalties (in relation to the reward) are also low, there’s very little incentive for builders to play by the rules. This is exacerbated when you throw deadlines into the mix – rezonings, 421-a sunsets, and the like encourage builders to play beat the clock.

Despite the fact that DOB has added new inspectors (and plan examiners), the department is clearly understaffed, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that complaints go uninspected. The City is in belt-tightening mode, so the prospect of a lot more inspectors is slim (though to its credit, the City has been adding a lot of inspectors in recent years). But beyond staffing, this is also a problem of priorities. “Nuisances” such as after-hours work are not a top priority for DOB. Life-safety issues (such as “my neighbor’s building looks like it might fall – on me”) are the highest priority, as they should be. The DOB’s list of complaint categories (pdf warning) says that after-hours work is a second-tier priority (category B). So too are issues such as working without a permit – another category of complaint that probably can’t be substantiated if its not investigated immediately.

Of course the city could just decide that a well regulated building industry is as important as as an efficient buildings department, and shift personnel from plan examination to inspection. That would result in a slow down in permitting and delays in building, which would not be popular in the real estate industry. Considering that construction is a major component of the New York City economy, and that the city continues to suffer from a shortage of housing, slowing down all construction to stop the small number of sites working illegally is probably not going to happen. But it is one option.

Its also worth remembering that DOB is an agency that exists to regulate building, not slow it down. Generally, it is in the city’s interest (economically and otherwise) to encourage building construction, not to stifle it. This is why the performance criteria for DOB is weighted towards streamlining the process. For instance, one area in which DOB showed improvement was in issuing permits – the average permit is issued in 5.x days in 2007 vs. 5.y days in 2006. That can mean that the system is more efficient, or it can mean that permits are being pushed through in order to show improvement. But either way, the department’s performance is noted as improving when they issue permits faster.

Given the reality of budgets, department mandates, inspection priorities, etc., can anything be done to improve response to quality-of-life issues related to building? There are a few things, actually.

- Get rid of the charade of “closing out” stale complaints. If there is a complaint for after-hours work that is more than 24 hours old, don’t send an inspector out – its a waste of time and money. Instead, admit that the complaint was not inspected, and close it out as “unresolved”. Then, flag the site for follow-up inspections. For the next 30 or 60 days, conduct random inspections of the site during evening or weekend hours. Don’t just do one follow up, do a series over the course of a month. This would not cost any additional money, and could be done by the existing cadre of inspectors as part of their normal evening and weekend rounds.

- Give other agencies the mandate to inspect and issue violations for certain class B complaints. NYPD can shut down a site for working without a permit, but they rarely do. Likewise, NYFD and other agencies with enforcement power could be brought on line. Maybe these issues are second tier for them as well, but having twice as many (or ten times as many) “inspectors” with this as a second-tier priority is still an improvement. This would not take any additional funding, it would only require that the higher ups make the issues a priority (albeit a second-tier one) for their personnel.

- Make it a policy that inspectors must get out of their cars and actually try to enter a building site. Sure, most inspectors are diligent, but sometimes its not clear from the street that there is work going on. They may be working in the back of the building, with the gate closed. Unless they are looking and listening, an inspector could easily miss illegal work in progress.

- Create inspection “hot zones” – flood neighborhoods with particularly high numbers of active building projects with inspectors on a regular basis. This idea – courtesy of Evan Thies – is akin to NYPD’s policy of flooding high-crime neighborhoods. Do random inspections during regular hours and sweeps on nights and weekends – if builders know that random inspections are a possibility, they are far less likely to be routinely flouting the law.

- Limit the number of after-hour variances by neighborhood. Either as a percentage of all work permits, or as a fixed number, limit how many variances can be issued on a given block or in a given Community Board.

- Exceptional cases aside, no site should receive more than one or two variances per month.

- Do not issue variances in areas that have been certified for rezoning. This last suggestion, and the two before it, are not blanket moratoriums (which would probably be unconstitutional). Unlike a building permit, an after-hours variance is a privilege, not a right. DOB should be handing out these privileges judiciously, and should not be doing anything to undermine potential rezonings. And once an area has been certified by city planning (DCP) for rezoning, it is pretty clear that some action will be taken. If there were a workable way to extend this moratorium to areas that are under study by DCP, that should be considered as well.

Again, just about all of these proposals could be carried out immediately without requiring any significant increase in funding or staff. Some of the proposals might require legislative action, but I think any action that is required would be on the City level and would not require going to Albany. These proposals – or others like them – would address immediate problems, and would put builders on general notice that inspections are going to be more frequent and more efficient.

Jackie Gleason

From Bushwick (who knew?).

Falling Down on the Job

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a link to the new nyc.gov Citywide Performance Reporting (CPR) system. In that post, I summarized the rather spotty performance of the Department of Buildings, at least as measured by the criteria of CPR. One number that jumped out at me was the 6% rate of violations issued against complaints for after hours work. It seems rather remarkable that citywide, 94% of complaints regarding after-hours construction could be unfounded. There are many reasons why complaints might not pan out – bad addresses, delays in inspection, malicious 311 dialing, and so on – but that all those reasons add up to 94% of the complaints registered for after-hours construction work is a tad mind boggling.

And as I noted then, because CPR does not report the number the total number of complaints, we can’t tell what the magnitude of the after-hours work problem is. Thus, it is impossible to tell what that 6% is 6% of. Are there dozens of complaints per year? Hundreds? Thousands?

Well as it turns out, DOB does issue reports on the number of complaints that it receives, and the number for Community Board #1 is 436. Citywide, the number of complaints per month (in all categories) is in the thousands – close to 5 figures in some months. For CB1, there were 3,854 DOB complaints in calendar 2007, which means that just over 11% of the complaints registered were for after-hours work (weekends and evenings). Wading through the data, it soon becomes clear that 6% is not the most pathetic figure (and if anyone from DOB wants to tell me how I might have waded astray, by all means drop me an email).

DOB only sort of reports on all of the complaints it receives. What DOB issues is weekly and monthly lists of all complaints received, with a coded resolution for each complaint. In terms of tracking complaints, the weekly reports are great; in terms of tracking complaint resolution, they are near useless. That is because DOB doesn’t always respond to complaints in the week in which they occur, and complaints that are resolved in following weeks do not show up in the weekly lists. The same things happens for the monthly list, but there is a bit less noise in the data, as DOB has more time in which to enter resolutions into their database. (You can, of course, look up complaints individually on BIS, which will tell you the resolution, regardless of whether it occurred in the same week or month as the complaint. Until I get an intern, I’m not looking up the status of 3,800+ complaints in CB1.)

This flaw in the data reporting is irrelevant when it comes to complaints for after-hours work, which makes this complaint category ripe for analysis. It is irrelevant because after-hour complaints are particularly time sensitive. If you call about illegal construction at 5:00 p.m. on a Sunday, an inspection at 9 a.m. the following morning is tantamount to no inspection at all. So unresolved complaints can be pretty safely lumped in with complaints that were inspected more than a day after the infraction – in either case, by definition an inspector will not see the infraction (unless those Priuses can travel back in time). This, of course, is not news.

There are other methodological problems. One is that the monthly reports list the date of the last inspection. So if an inspector does happen by, and issues a violation or stop work order, and that order is then lifted a week later, it is the lifting of the order that appears on the monthly report. And the date of the lifting is the date of the last inspection, making it appear that DOB took a week to get to the site. But because the number of resolved complaints is relatively low, its actually fairly easy to weed these problems out.

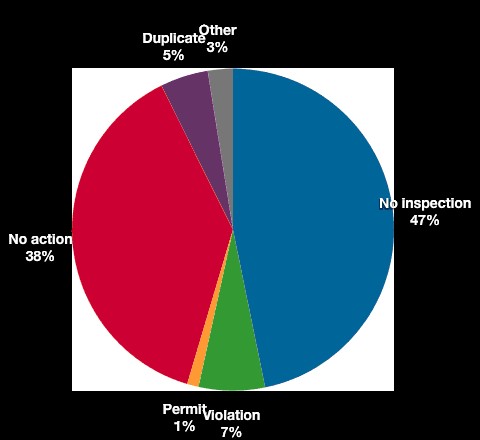

CHART 1: CB1 after-hours complaints, 2007

(Source: DOB, unadjusted numbers based on monthly complaint disposition reports)

So of the 436 complaints in calendar 2007, how many wound up being inspected? A rather disappointing 53% (see Chart 1). That’s right, almost half the complaints logged were not inspected in the month in which the complaint was made. Which means they might as well stay uninspected.

Further, 38% (166) of the complaints resulted in no action. If you look up the complaints, you’ll see that this was usually because the inspector found no illegal work in progress at the time of inspection. But you’ll also see that the vast majority of these complaints were not inspected for days. Which means, once again, they might as well have not been inspected at all.

When you combine thsee uninspections with the noninspections, fully 77% of the complaints for after-hours work turn out not to have been inspected in a timely manner. Is it any wonder that only 6% of complaints citywide result in violations? At a maximum, 25% of all complaints are inspected in a timely manner (i.e., in a time frame in which its reasonable to expect that the violation might still be occurring). On that basis, DOB has a slightly more impressive rate of violations of 30% (sure, its 30% of 25%, but still, it looks better). Although at least in CB1, the majority of the violations issued actually have nothing to do with after hours work. Instead, inspectors wind up issuing violations for other infractions. All told, only 11 stop work orders were issued in all of 2007 for after-hours work. In CB1, chances are there are at least 11 sites operating illegally on any Sunday.

What of the other complaints that were inspected? Another 30 cases (31% of “good” inspections) appear to have been inspected on the date that the complaint was logged and no illegal work was found. Based on a random sampling, about a third of those wind up being sites that had a variance for after-hours work, and were miscoded in the system. So in reality, there are probably 20 or so complaints that were inspected on a timely basis and turned out to be truly unfounded. Only 5 cases (5% of “good” inspections) turn out to have variances for after-hours work (add to this the misreported variances mentioned above, and you get up to about 15%). Another 22% (21 cases) are coded as “previously inspected”. In many cases these represent multiple calls on the same day, but (again, based on a random sample) in about 1/3 of those cases, the complaint was for a completely different day. So add those (7 or so) cases to the list of “noninspections”. The remainder (about 10% of “good” inspections) fall into “other” categories – complaints referred to other agencies, bad addresses, sites where there was no access).

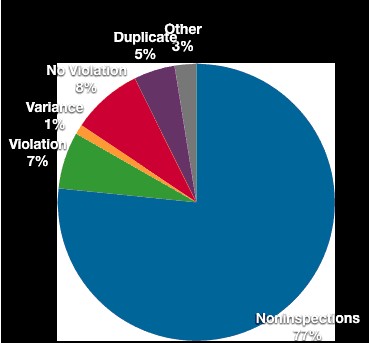

To recap, in CB1, where there is a construction site on every block, there were 436 complaints for illegal after-hours work in calendar 2007. Just over 75% of those complaints were not inspected in a timely fashion (see Chart 2), and roughly half were not inspected at all (or at least not in the same month as the complaint was made). As a result, the vast majority of the inspections that are made result in resolutions that say “No illegal work at the time of inspection”, though clearly the (alleged) illegal work was going on the weekend before (or the night before) said inspection. Just under 7% of the inspections result in violations or stop work orders (not always for after-hours work), and a like number are inspected in a timely manner and turn out to be (truly) unfounded complaints. Just over 3% of the complaints were for sites with legitimate after-hours variances. About 5% of complaints are recorded as duplicates (although many of then aren’t); just under 3% fall into the “other” categories.

In this light, 6% doesn’t seem so pathetic.

CHART 2: CB1 after-hours complaints, 2007

(Source: DOB, numbers based on monthly complaint disposition reports, adjusted to

reflect timeliness of inspections)

Cats Save Lives (Dogs Don’t)

Apparently, Miss Heather will live forever.