Nice article and photos on the newly-opened 50 Kent parcel at Bushwick Inlet Park. Include the anti-geese coyotes. I’m not sure how the geese know the difference between coyotes and dogs, but whatever. (Also, really hoping that the actual dogs – and their owners – don’t ruin this space.)

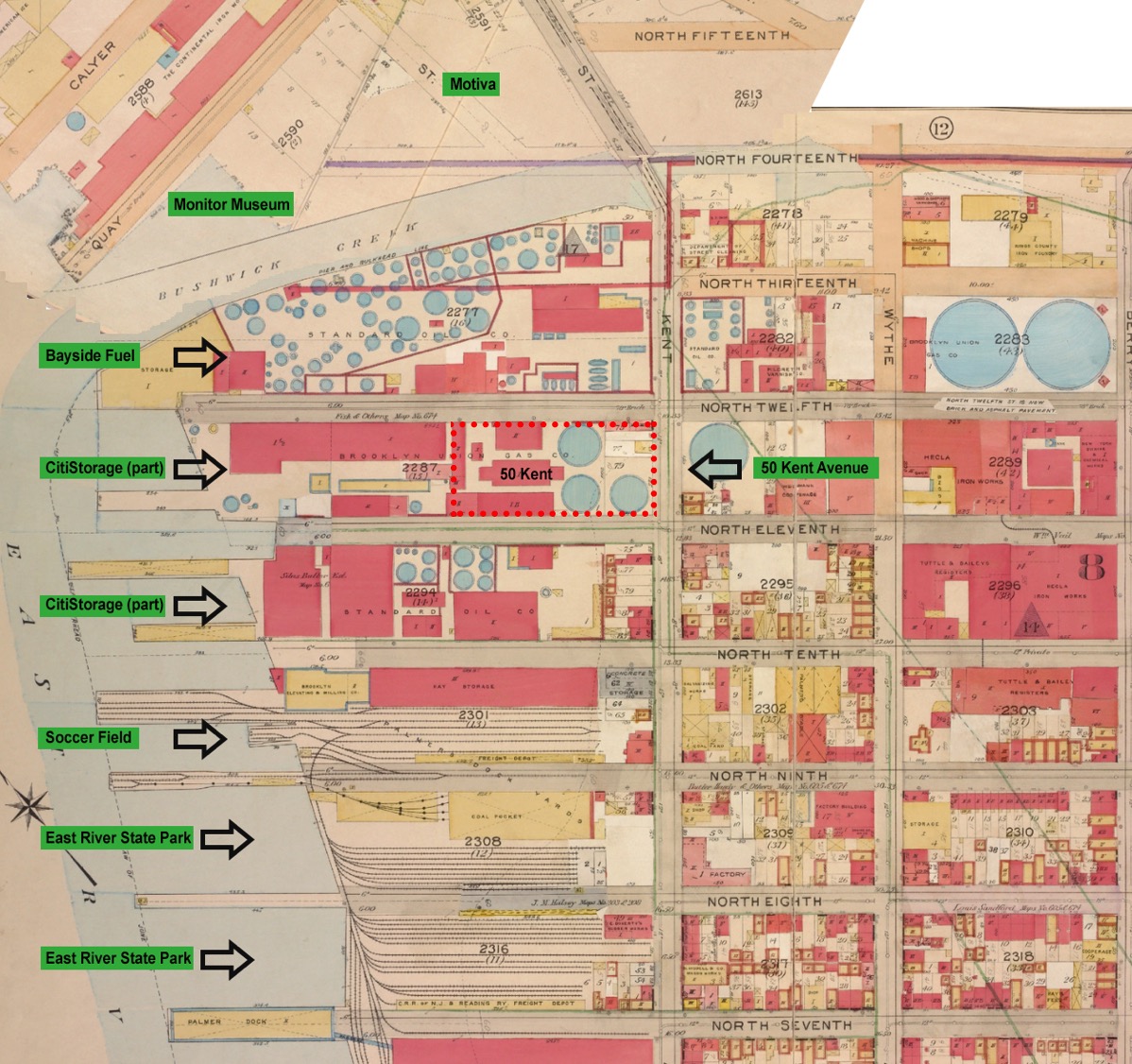

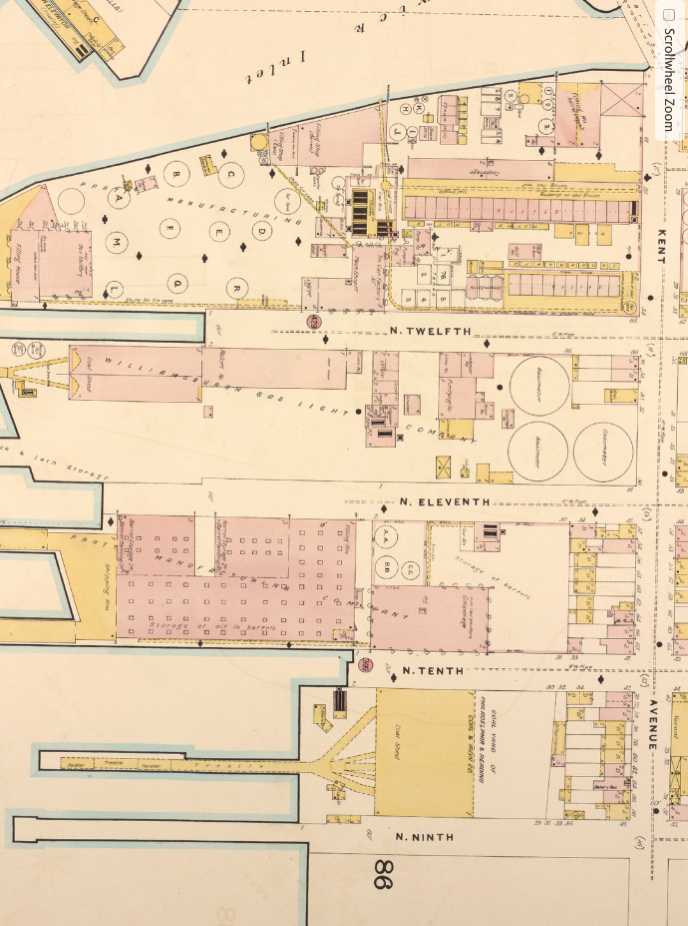

For those of you keeping score at home, the new piece of the park is just under 2 acres, and represents about 7% of the future full park buildout (27 acres). To date, just under one-third of park that was promised in 2005 is completed and open to the public. That works out to about half an acre of park per year.